Michell-Hedges lived on his boat, the Amigo, anchored off Rocky Point, Helene, for several years in the late 1920s. That was until one day, when his fellow explorer Dr. Ball, surveying on Bailey’s Cay, observed his compass needle spinning wildly. The duo dug down and discovered four chests loaded with doubloons and jewelry, which they re-crated as Indian artifacts and then fled the islands in haste. Once in America, it was purported that he sold all the booty for $6 million. Michell-Hedges also booked himself up on a speaking tour of the US, Canada, and Britain.

While on this speaking tour, the account of his amazing discoveries in the St. Helene and Barbarat brought the attention of professional archeologists, particularly of his claims that the artifacts were the remains of the lost city of Atlantis and some 25,000 years old. The first serious Archaeological trip was the Boekelman shell heap expedition of 1931, which focused on shell heaps or middens as an indication of population centers. The most fascinating and well-documented expedition was the Duncan Strong trip of April and May of 1933 to Utila (Roatan’s Dixon Hill site), Port Royal, St. Helene, Barbarat, Morat, and Bonacca.

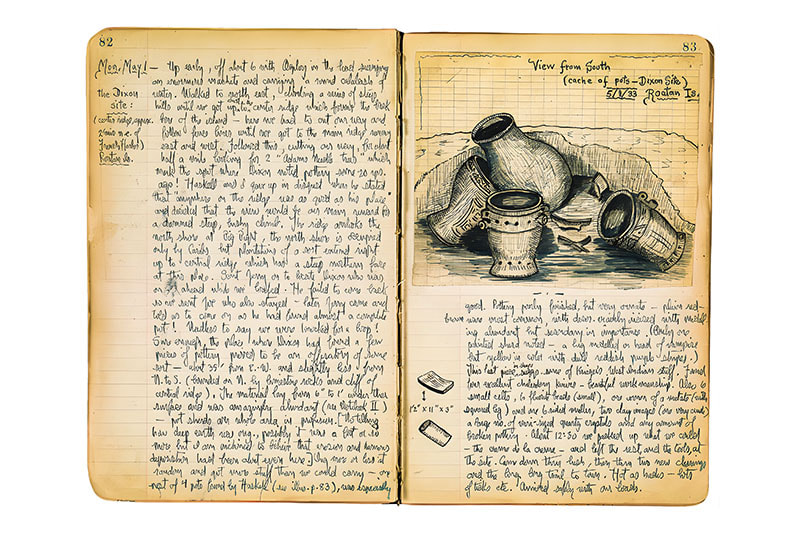

Strong’s notebook is quite a delight to read, with some beautiful sketches of flora and fauna as well as artifacts found at the sites. It is a delightful combination of Natural History and Archaeology. Strong’s expedition had a distinct advantage in that he used the same MV Amigo with the wooden legged Captain Frank Boynton, and with it the same crew – Gerald Bodden and Joe Solórzano – that had accompanied Mitchell-Hedges a few years prior. On Roatan, he explored a site on a hill East of French Harbour on Dixon land, accompanied by Ogilvy Dixon, which he called Dixon Hill.

Strong’s book—the result of his 1933 expedition, “Archaeological Investigations in the Bay Islands, Spanish Honduras”— is still considered the starting point for any archaeological or anthropological study of the Bay Islands’ pre-Columbian history. More significantly, Strong was not only an academic with a Ph.D. but also an Americanist through and through.

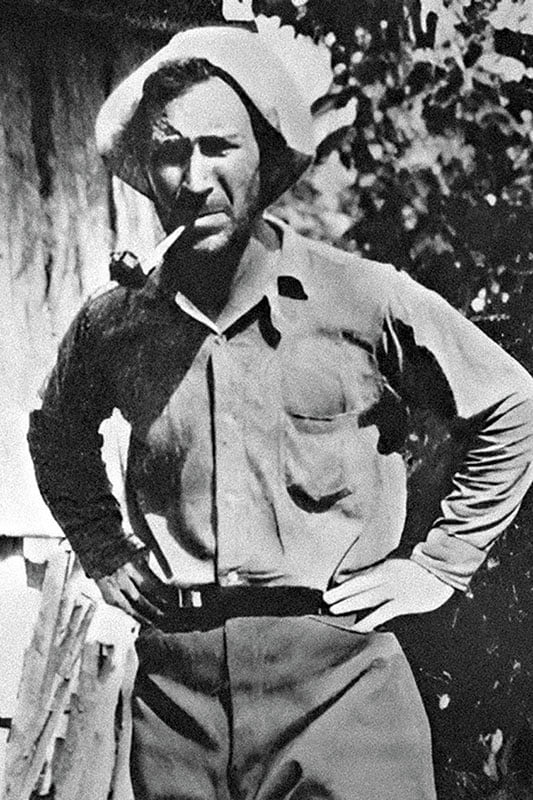

He is widely credited with introducing modern archaeology to Columbia University, where he served for many years as chairman of the Department of Anthropology. An assiduous field worker and influential theorist —not a showman like Mitchell-Hedges— his journal and book provided a trove of information on Bay Islands history that formed the basis for two subsequent expeditions in 1938 and 1939.

At about the same time that Duncan Strong was exploring the hills and caves of the Bay Islands, Walter Edward Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne, completed his purchase of the SS Dieppe and refitted it as a diesel-powered private yacht, which he named MY Rosaura.

Guinness was a soldier, businessman, and conservative politician renowned for building the Guinness brewing empire in Dublin —a venture originally started by his grandfather. In addition, he was a close friend of Winston Churchill, who, along with his wife Clementine, was among the first guests aboard the Rosaura during a summer 1934 trip to Greece and Beirut.

Later that year, the Prince of Wales, the abdicated King Edward VIII, and Wallis Simpson also became his guests. Wallis later wrote that it was during their voyage together on the Rosaura in the Mediterranean that she grew to love Edward.

Lord Moyne began his political career at the age of 27, and over 37 years he advanced from Member of Parliament to the House of Lords while holding five cabinet positions—primarily during Churchill’s wartime leadership. His political journey eventually brought him to the Caribbean when Neville Chamberlain appointed him Chairman of the West Indies Royal Commission in 1938.

There had been widespread labor unrest in the British Caribbean, and Moyne was appointed to spearhead reforms in the region. As an explorer and artifact collector, it was natural for him to travel aboard his boat, MY Rosaura. He made one trip to the Bay Islands in 1938 and another in 1939. He had been inspired by Strong’s Journal and by Mitchell-Hedges’ Land of Wonder and Fear. Notably, prominent archaeologist Eric Thompson commented on Mitchell-Hedges’ work, stating, “To me the wonder was how he could write such nonsense and the fear of how much taller the next yarn would be.”

Michell-Hedges lived on his boat, anchored off Rocky Point, Helene.

Captain Frank Boynton, who had accompanied Mitchell-Hedges as his pilot, was assisted by two men: ‘Spanish Joe’ Savas Solórzano and Gerald Bodden. Both men hailed from Diamond Rock as crew of the Moyne expedition of 1938. They didn’t spend much time on Utila or Roatan and made it straight to Helene. There they met Thomas and Herbert Forbes, who were instrumental in revictualing the Rosaura and served as guides on Helene and Morat, alongside Cleveland Bodden and his two sons, Marwick “Butterfly” Bodden and Telford Bodden. I should mention that I knew “Uncle” Butterfly during the last few years of his life and learned much about Helene’s history from him.

The sites that Moyne and his group excavated extensively were on the three peaks of Indian Hill on Helene. Over a thousand pieces were removed from this area and now sit in the British Museum (and can be viewed on their website). Some quite uniquely painted ollas with tripod legs – typical of artifacts found in the Ulúa valley – tell of a distinct link between the Bay Islands Payan Indians and the settlements in Ulúa.

On board the Rosaura for the 1938 expedition was the renowned Zoologist, H W Parker CBE, keeper of Zoology of the British Museum. He is known for discovering and naming a new species of Gecko, the Bay Islands Least Gecko, or its latin name, Sphaerodactylus Rosaurae (in honour of the Rosaura ). Lord Moyne’s patronage and Parker’s association with the British Museum would explain why all of Moyne’s pieces from all over the world ended up here.

In the summer of 1939, R. W. ‘Dickie’ Feacham, an Archeologist who had accompanied Lord Moyne on a prior expedition to Greenland, had managed to arrange backing from the Royal Geographical Society and the Faculty of Archeology at Trinity College, Cambridge. The Rosaura was to be used with Lord Moyne tagging along from Jamaica, no doubt to clean up where he had left off with his looting of Indian Hill on Helene.

This was the summer of 1939, and war clouds were gathering in Europe. It was rumored that Moyne’s close friend Winston Churchill would replace Neville Chamberlain as Conservative leader, and would likely call upon him to serve in his cabinet. However, not only did impending war loom, but the sudden death of his wife, Lady Evelyn Stuart, on July 31, 1939, force Lord Moyne to depart for England on the Rosaura. Meanwhile, Feacham and his entourage continued aboard the Amigo—Capt. Frank Boynton’s vessel, which had been used by Mitchell-Hedges in 1927.

The expedition began in Utila, where they briefly retraced the steps of Junius Bird and William Waterhouse’s 1929 Smithsonian expedition. During their stay, they revisited the Indian Well, a stone causeway, and several urn burial sites with local guide Eddie Whitefield.

From Utila, they ventured west, roughly following Strong’s 1933 expedition trail, and stopped at Pollatilla and Punta Gorda. There, they observed that the village —with its thatched huts, cows, and pigs— resembling Wiltshire with palm trees. On Helene, accompanied by Cleveland Bodden and his sons, Butterfly and Telford, Feacham and his crew explored the same caves that Strong had examined in 1933. These caves bordered the mangrove canal where Mitchell Hedges had supposedly found the Crystal Skull.

A visit to the Indian Hill site revealed nothing except for shards of pottery left by Moyne the previous year. Further west on Barbarat, guided by plantation men Wesley and Brindley Cooper, they trekked up Pear Tree Gully to Indian Hill, where they found a few artifacts —most notably, a large egg-shaped vessel with three legs and a hole at the bottom. The expedition concluded at Bonacca, where they met Professor Colin Pinckney from Cambridge University, who, along with Derek Leaf, was surveying the walled site at Plan Grande.

Interesting things happened to Lord Moyne and MY Rosaura. In 1941, MY Rosaura was commissioned by His Majesty’s Navy as a boarding vessel and renamed HMS Rosaura. A few months later, on March 18, she struck a mine off Tobruk and sank, claiming the lives of 78 people.

Lord Moyne was appointed leader of the House of Lords in February 1941 and Secretary of State for the Colonies. In February 1942, Churchill named him British Minister Resident for the Middle East in Cairo, Egypt—a position he held until his assassination by members of the Jewish ‘Lehi’ terrorist group in November 1944, an attack that also claimed his driver’s life. This event marked the beginning of the end for British influence in Palestine, and for once, upon hearing of his friend’s death, Winston Churchill fell ill and was unable to address Parliament.

The Moyne Collection is still housed at the British Museum, and I suspect it would be well worth the effort to repatriate it to Roatan for display in a future museum. Meanwhile, the Rosaura now rests in 200 feet of water off Tobruk, and its namesake, the Sphaerodactylus Rosaurae, continues to roam the forests of Roatan, munching on insects.