I jumped at the chance to write about Bay Islands history, of course, when Chas Watkins asked me to write a foreword to his latest book. Besides writing, I derive great pleasure from researching and sharing my findings. Many academic papers have been written about our anthropology and geology, but much remains unknown or unsolved thus far.

We don’t know exactly when the Bonacca Ridge was formed, and we still don’t know if the Paya Indians were indeed the only Indians to have lived here. Besides being a longtime resident for the past 17 years, Chas shares my curiosity about our history, among other things. Having lived here since the relative beginnings of the development boom, he has seen much change and has a lot to share from his experiences and local knowledge.

The original inhabitants prior to the Europeans were most likely the Paya Indians. This is a conclusion disputed by many archeologists during the 10 known expeditions to the islands since 1924. There is evidence of the presence of Maya, Lenca and Jicaque aborigines in the Bay Islands; however, the strongest evidence points to the Payas, specifically a group originating south of Trujillo.

Evidence unearthed by Islanders in recent history points mostly to residential sites, but also to offertory, burial and some ceremonial sites (interestingly, the largest and most significant being a 40-acre site on Utila and a several-acre site in Plan Grande, Guanaja). “Yaba Ding Dings” (Indian artifacts) being a common find throughout the Bay Islands drew amateur archeologists as well as looters to the aboriginal sites. Sadly, the first Bay Islander’s idyllic lifestyle of fishing, farming and turtling started its decline with the arrival of the first Europeans and with Christopher Columbus’ fourth voyage in 1504.

Augusta in Port Royal was part of this ‘Royalization’.

Slowly, the Spaniards began to take control of the Indians’ lives, and they were subject to the same treatment as other indigenous peoples in accessible locations the world over for around 136 years, first being raided and enslaved, Christianized and then exploited as laborers.

Their legacy today are the old pieces of pottery jars strewn around the hills of the Islands. There are a few interesting monoliths in Guanaja and their names, which could be where the three island names originated: Wa-nak-ka (Guanaja), the modern Payan word for ‘cloud’; Arroa or Roata (Roatan), modern Payan for ‘Pine’; and Uu-tia (Utila), meaning ‘sand-water.’ It was not until 1638 that another European Imperial power, the English, challenged Spanish control of the region.

It was when the Puritan settlement of the Providence Company under William Claiborne and a group of English and Scots emigrants from Virginia and Maryland settled in what is Old Port Royal today. The colony, however, was short-lived. It lasted just four years, and besides Claiborne’s cousin, Captain Butler, making a nuisance of himself by burning down the four Indian towns in the islands and creating strife with them, England was in the midst of a civil war, and as a result, there was no protection available in the Caribbean.

By the end of 1642, most of the settlers were evicted, and the islands remained sparsely populated, with the only inhabitants being the few remaining Paya who had not died, run away to the continent or had been enslaved. A few English settlers who had remained turned to darker ways and joined in the wave of piracy that was sweeping the Caribbean, filling the power vacuum left by the Spanish and English.

Nelson was stationed in Port Royal.

There is much commercialization of the fact that the Bay Islands were once frequented by buccaneers. The name of the infamous Henry Morgan is used frequently, but it is disputed that the Bay Islands were his base of operations. It is more likely he just passed through to collect water or victuals or careen his vessels on more than one occasion.

Two of the most notorious pirates who were known to have used the islands were Blackbeard (Edward Teach or Thatch), who would careen his vessel Queen Anne’s Revenge at a shallow bar east of the airport called Thatch Point, named after him. The other notoriously violent pirate who made Roatan his sanctuary was Edward “Ned” Lowe, whose ghastly cruelty was documented by Philip Ashton, who escaped Lowe on a victualing and water supply trip to Port Royal and was subsequently marooned, escaping certain death.

The young Ashton spent two years between islands until rescued, and his story is included in Edward Leslie’s, Lost Journeys, Abandoned Souls. Many other buccaneers were rumored to have passed through since the islands were ideally positioned as a refuge after attacking Spanish ships carrying Indian treasure looted by the conquistadors from the Spanish Mainland. Names like John Coxen (after whom Coxen’s Hole is named), Morris, Jackman, Van Horn, Uring and L’Ollonais, who fixed nets, made rope from Macoa and fished for turtles when not pillaging and creating havoc.

The Bay Islands were a no-man’s land at this stage in their history for around 100 years, no more than a victualing station and temporary base for pirates, log-cutters and the odd Paya Indian survivor. At the outbreak of war (the War of Jenkin’s Ear) in 1739, England was looking at bases in the region, and the Bay Islands was one such area.

In 1742, 250 soldiers and slaves landed in Port Royal and started to build fortifications. Later, families of the soldiers were brought in to populate the area, and records show that the population in 1744 stood at 1,000. The town of Augusta in Port Royal was part of this “royalization,” with farmland being cultivated and even a cooperage set up operations.

Some settlers found the red land and oak hills unsuitable for agriculture. With William Pitt’s (the first civilian superintendent and cousin of the future prime minister of England with the same name) blessing, they moved to the northwest coast of the island to Anthony’s Cay (today Key) and began to cultivate 100 acres of flatter, more fertile land.

This occupation ended in 1748 with the signing of the Aix-la-Chapelle peace treaty, and the last troops left in 1749. The island once again remained abandoned with no record of any permanent settlement until 1779 when war broke out again.

Colonel Dalrymple was ordered by Jamaica to once again occupy Roatan and the Bay Islands as part of a larger English strategy to dominate the region, which included attacking Fort San Juan with disastrous results. A young Horatio Nelson participated in this raid and nearly died of malaria. Nelson was stationed in Port Royal for half of 1778 and performed anti-piracy patrols of the Western Caribbean on his first command, HMS Badger.

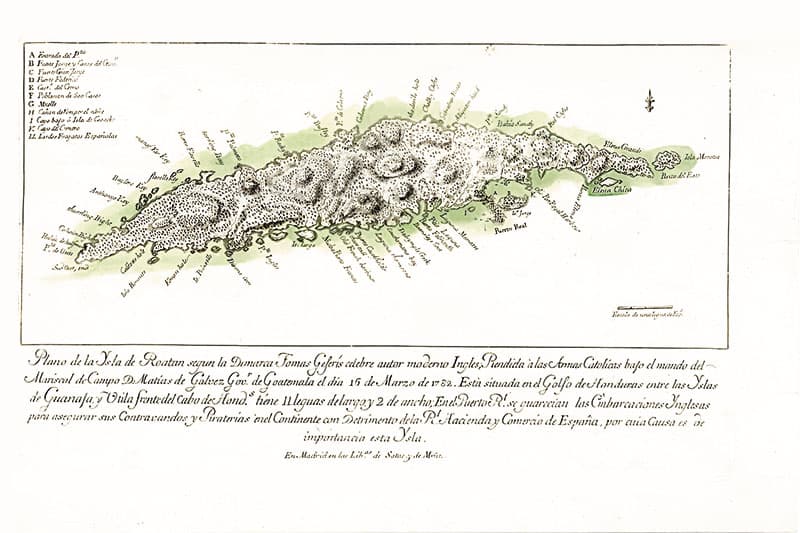

Omoa on the mainland was also attacked and occupied by His Majesty’s forces for a brief time. English presence in the region was eventually weakened, and the last English stronghold at Port Royal was attacked by a combined force from Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua under the leadership of Guatemalan President Matías Gálvez, who attacked on March 16, 1782. The English, seeing that they were outmanned and outgunned, scuttled their only ship in the main channel to impede the Spaniard’s access to the harbor. The fighting went on for 48 hours, and despite a valiant effort, the Spaniards were victorious. The Spaniards made a few futile attempts to populate the islands after the battle, but were mostly unsuccessful.