A smaller group stayed behind in Punta Gorda, where they remain to this day a thriving, dynamic community.

Gradually, the Garifuna diaspora spread all over the Central American coast of the western Caribbean, from Livingston in Guatemala to Puerto Limón in Costa Rica. Here on Roatan, Punta Gorda remains a compelling place to visit with unique foods, dancing and their unique language, which contains some French and English words. Until recently, most houses in PG, as it is popularly known, were wattle and daub with palmetto thatch. The Garifuna culture revolves around fishing using handmade dugout canoes with a small amount of subsistence agriculture, but with the recent influx of visitors, most of the economy revolves more around tourism.

The second most important permanent settlements were of enslaved people and slave owners who originated mostly from Cayman and Belize, beginning in the 1830s, mainly after 1834, when slavery officially ended in the Cayman Islands. The Bay Islands population rose exponentially every year and peaked in 1844.

In 1838, with the overwhelming influx of English-speaking settlers, the Spanish authorities declared that all settlers should apply for residence with the authorities in Trujillo. This created some dissatisfaction, at which the settlers appealed to the Superintendent of British Honduras (Belize), Col. Alexander McDonald.

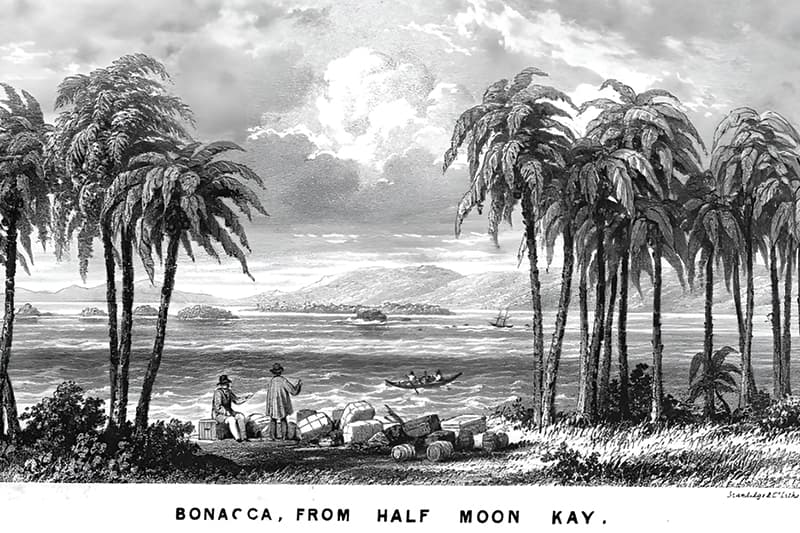

Bay Islands were a center for agriculture in the western Caribbean.

Claiming harassment by the Spaniards, McDonald, a fervent patriot itching for a chance to mix it up with the Spaniards, preceded to Roatan, where at Port Royal, he landed and proceeded to lower the Central American flag and raise the Union Jack. No sooner had he sailed away than the Spanish Commandant, Juan Bautista Loustrelet, lowered the Union Flag and hoisted the Central American flag again. This act so infuriated McDonald that he returned, clapped the Spaniards in irons and sailed them to Trujillo, where he abandoned them on the beach and warned them never to return.

The English settlers enjoyed this protection and were helped in part by the fact that the newly independent Honduras had its own problems of nation-building on the mainland. The islands flourished and even had their own local government set up by the English authorities from Belize. Settlements were formed coastwise around the islands in Utila and Guanaja and on Roatan in Flowers Bay, West End and Jobs Bight, with the main center of population gradually becoming Coxen’s Hole, while Port Royal became less popular and eventually abandoned until the 1960s with the arrival of the first group of expatriate Americans and English.

In 1852, the Bay Islands were recognized as a Crown Colony, and the population under British protection thrived with communities popping up everywhere. By 1858, their numbers reached nearly 2,000. The Bay Islands were a center for agriculture in the western Caribbean and the mainland; boat building began as a Bay Island industry. Sadly, or tragically if you ask a modern-day Bay Islander, pressure was mounting from the U.S. Congress, who claimed that Britain’s incorporation of the Bay Islands as a Crown Colony was in direct infringement of the Monroe Doctrine and by default the Clayton-Bulwer non-colonization treaty.

Britain was forced to cede the Bay Islands back to the Republic of Honduras, an island whose languages and culture were English and Garifuna, not Spanish. Although disappointing, this didn’t really impact the Bay Islanders, who kept flourishing with little interference from an indifferent, incapable central Honduran government.

The island economy diversified from agriculture to shipbuilding and commercial fishing. Growing up around the sea, islanders were excellent seafarers, and beginning in the 1930s, many “shipped out,” taking well-paying jobs on merchant ships, later oil field supply vessels and river-going tugs around the U.S. and the rest of the world.

Some of these adventurous seamen stayed off on the Gulf Coast and learned about shrimping and came back in the 1960s to start up what was to be the largest fishing fleet in the Caribbean. This initiative and tenacity eventually led to the beginning of the dive industry in the Bay Islands.

This later led to the construction of the first cruise ship terminals, which became the catalyst for the development boom in the late 1990s, bringing with it newfound opportunities, industries and prosperity. Many of the descendants of those English and Scottish immigrants or freed slaves with names like McNab, Elwin or Bodden are building your houses or checking you in for your flight back; maybe a smiling young Garifuna lady is taking your order at a seafood restaurant. This is where they have come from.

And what of the old nemesis, the mainland Spaniard, once the foe of the English? They are now here to stay, completely integrated into our melting pot of a community.

With the beginning of development in the 1990s and demand for skilled labor, mainlanders came to the islands in droves and planted roots, much like the 1830s settlers. They thrived, and the second generation of these settlers are now born islanders who speak English and make up around 60 percent of the population.